Visual Illusions and the Nature of Visual Experience

A brief introduction to seeing

In the last few months, I’ve had some real joy and benefit from reading posts by and engaging with the philosopher, cognitive scientist and meditation teacher Pete Mandik. A good example of a post I find useful is the recent “Take Mandik’s Imaginary Purple Banana Challenge”, which actually does a lot more than what first meets the eye. The post accurately claims that the challenge provides you with a chance to “learn something deep about your mind”. By learning what is going on when you are imagining purple bananas, you can actually learn something important about what it means to be a subject having experiences.

As powerful a pointer as the challenge is, I suspect the hill is just too steep for many to climb. This post is, among other things, is meant to serve as an accessible quick-start guide on how to use Mandik’s banana challenge to learn aforementioned deep truths about yourself. On our way to get there, we will hopefully gain a few other useful insights. Now, if you haven’t already taken Mandik’s banana challenge, please do so before continuing. This post will be waiting for you right here.

Welcome back. If you figured it out, congratulations! You don’t really need to read the rest of this post. I suggest you instead test your new insights against this related post of mine, or this great Mandik post on what meditation does and doesn’t do.

However, if you are not yet enlightened by taking the banana challenge—don’t worry, we’ll get you there. We’ll return to Mandik’s challenge in a bit, but for now, a detour is necessary. We will employ some so called visual illusions to aid you in our path towards seeing the truth. First, we’ll just go through a few of them fairly quickly, but we’ll discuss them later, as well as look at a few more.

Visual illusions

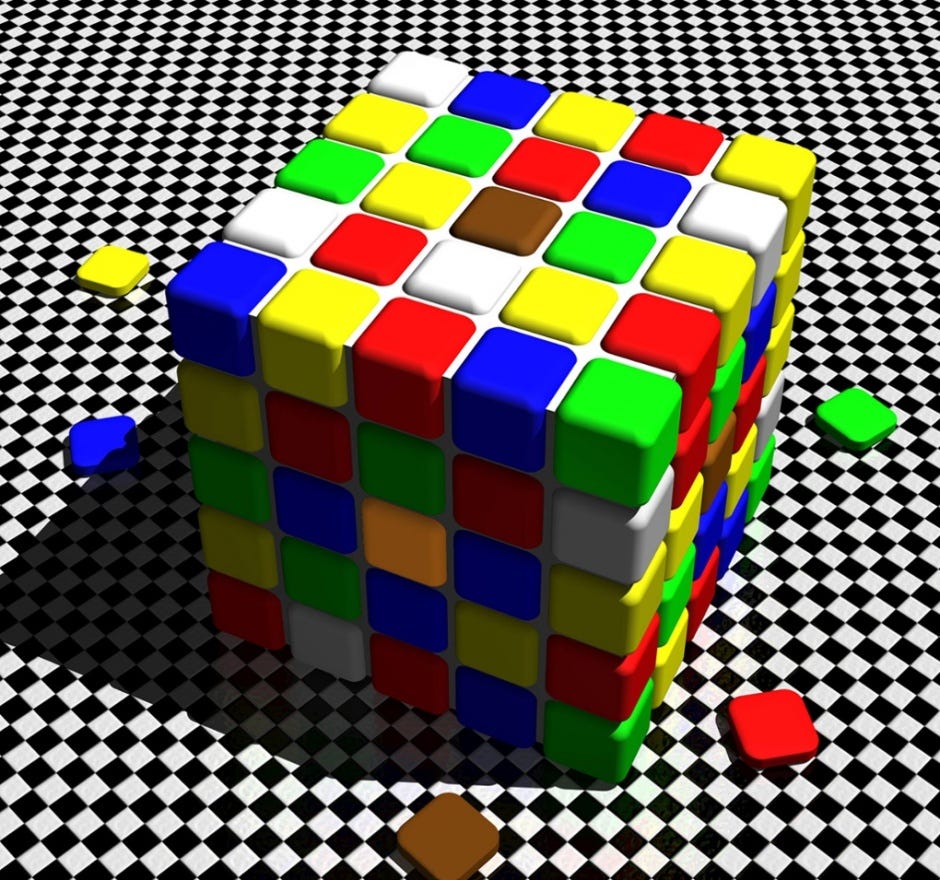

Here, the orange tile on the lower left pane is the exact same colour as the brown ones (that may be a contradiction in terms, but never mind for now!). If in doubt, here is a demonstration that the orange tile is in fact not an orange tile (?). What is going on here? When you’re ready to move on, go to the next illusion.

Oh, I love this one! Both face skin colours are the same shade of…grey? Of something, anyway. If you doubt it, look at this cool animation by Vitaliy Kaurov (source):

Instruction: look at a point in the middle of left gal’s face and follow that point as it moves. Use your finger or mouse pointer if needed. After the faces join and start splitting again, be sure to follow that corresponding point as it moves to the right. Then reflect in this manner: does it seem like the colour at that moving point ever changes? If you’re like me, it doesn’t ever seem like the colour changes at the point I’m focusing on. As the faces split, it doesn’t really seem to me like the colour actually changes anywhere else either. However, the judgement that the two faces have very different skin tones colours very clearly gets more vivid as the faces split. How is this possible? No change, and change, simultaneously? Hmm. We must move on. Here is the next illusion…

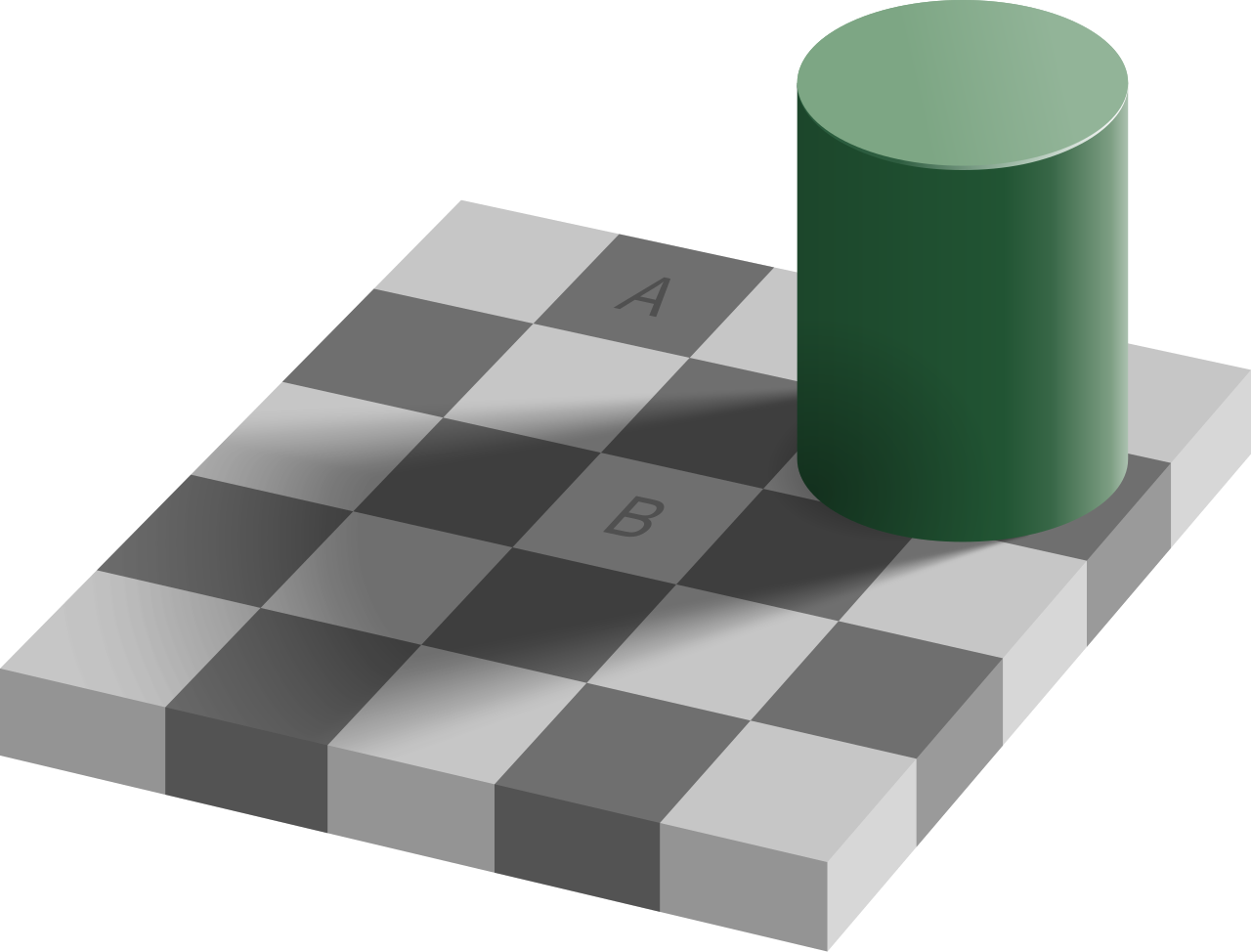

The checker shadow illusion by Edward H. Adelson hit humanity in 1995, and it’s probably the most famous of all colour/shade illusions. Here, the A and B squares appear as two distinct shades of grey, while, in fact, they are the same (?). Pretty cool!

I don’t know about you, but if I stare at B1, I can quite easily make A and B (and the would be C at the bottom) appear as the same shade of grey. This shifts back and forth. If you can’t make it happen, maybe the animation below will do the trick.

Here’s a cool animation by wikipedia user (3ucky(3all that nicely demonstrates this “same, same, but different” effect:

If focusing my gaze on B: on one hand, I get a back and forth between A and B being the same, while on the other a sense that B is clearly brighter than A on the other. While experiencing this back and forth, it simultaneously does not seem to me like the pixel brightness is actually changing anywhere in A or B. Again, it’s a weird change and not-change at the same time. What about you?

In contrast, If I stare at A instead, then B sometimes seems to become brighter before my eyes—but not every time, and not very convincingly.

What is going on in all of these illusions? Next, I will present two suggestions on how to interpret the goings-on in all of these illusions.

First way

The first way is simple enough. Let’s begin by with the animation of the checker shadow illusion. When looking at the grey shade in at the start of the animation, it’s clear that A and B are the same shade of grey. In other words, it seems clear enough that there is a particular shade of grey2 displayed on the screen, and there is a particular shade of grey experienced in your mind.

So what goes on when the animation continues and A and B transform from looking similar to looking different? For some reason that probably has something to do with how the brain interprets the shadow in this particular illusion, suddenly there seems to be two distinct shades of grey. There isn’t really, of course, out there on the sceen, as we have been shown. But in your mind, there certainly are two particular shades of grey being experienced. (You may not be able to say exactly which shades they are, because words cannot convey that, but there are two shades in your mind, as is terribly easy to confirm by simple introspection!)

As a side note, this view raises a few issues. For example: post-transformation into two shades, do you experience two completely new shades, or does one turn into the other? Perhaps it varies depending on where you start looking? Also, is there a certain number of different shades of grey that the brain or mind can generate for experience, or are there infinite shades?

You may posit that such calling this “issues” are simply mistaken. This is about subjective, first-person experience. You may think that this is simply a realm that is not accessible to the quantitative analysis and descriptions of the natural sciences. You may even go so far as to say that neuroscience has not even begun to give any remotely plausible account of this works. Science may be able to explain how the brain identifies grey, but not how it experiences the greyness of grey!

If this line of thinking seems right to you, do your best to internalise it, and go take the banana challenge again. If you fail, you’re most welcome back!

A possibly better way

If you failed, or if you want to evaluate both options before committing, let’s go through the second option. Let’s begin by asking ourselves what we would expect natural selection to result in; in other words, what has historically been important.

Has it been important humans to be able to directly apprehend differences in screen pixel shade values when viewing checker-boards? Or is it perhaps something else that eyes and brains have evolved for?

It is something else. Eyes and brains have evolved for accurately, quickly, and energy-efficiently getting a grip on the environment and one’s place in it. This includes all the important details in scenery, static objects, friends, enemies, prey, various internal signals, and so forth3. However, it is important to recognise eyes and brains have definitely not evolved to understand how they do this. If you know anything about evolution and biology, it should not be a surprise to you that you cannot introspectively figure out how it is done!

It’s time again for a visit to thought expreriment land and a bonus quiz!

(we’re still in the “possibly better way” part)

Instruction: imagine you are part of a cave-man/woman tribe in which accurately shaded checkerboards are among the highest valued objects one can own (not unheard of in this land). One day, while exploring, you encounter incredibly impressively made wooden table in the middle of nowhere, on which something that resembles a checkerboard sits, but with a unique 8x7 squares layout and made from a strange material. There is also an even stranger green-and-shiny object that no doubt—you think to yourself—is created by the Gods.

You’re in a rush to get back home, and you don’t have time to inspect the checkerboard-like object closely. You must quickly make up your mind whether picking it up is worth the risk of angering the Gods. If it is not an accurately made checkerboard, it is certainly not worth the risk! If it is an accurately made checkerboard, you would happily take the risk of immediate death (that is how highly you value checkerboards!).

Question: is the following checkerboard-like object a reasonably accurately shaded 8x7 square checkerboard? Does it have two different shades—no more, no less— arranged as they should be? (no two adjacent squares of the same shade).

What would your judgement be?

Now, please vote! (this is the quiz, of sorts, but mandatory). If you think this seems easy, good! This is not a trick question. You got this!

If you answered ‘yes’, congratulations. You have well functioning eyes, and a well functioning brain.4 Why? Because your eyes and brain correctly determine that the part of the board darkened by the shadow is not actually darker. There’s just a shadow there, and you correctly determine that all the squares are painted in only two colours.

Insight: should you care about the number of photons hitting your retina? Of course not! The eye-brain system is optimised to determine facts about the world out there. Not on the retina or in your mind.5

Here’s an edit of that same image after some copy-pasting fun:

Can you figure out which square is copied from which other square? There are five, so one is not copy-pasted at all. Next paragraph reveals the copy-paste sources.

…

…

…

A has been copied to B, and E has been copied to D. C has not been copied at all. Why does B look like a bluish dark square? And why does D look more like the light grey C square than the dark grey E square that it actually has been copy-pasted from? These strange effects come from the simple fact that we have not copy-pasted the actual squares, out there, in the world. If we’d done that, things would look perfectly normal. Instead, your brain is doing its best to figure out which colour the various squares would have out there, on the board.

The main lesson to take home from this is that visual colour experience is always conceptual and relational. But this lesson is not limited to colour—the exact same principles apply to shapes and relative sizes6. Here is a great example of the latter:

All three cars are the same size in the image, which translates to the same size on the screen, and on your retina. But recall—what does the brain care about? As before, the brain cares about what’s true about the cars out there, in the world. If you were not looking at a screen, but instead directly at what this photograph depicts (if it were real, in front of you), then the cars would still be the same size on your retina. For obvious reasons, brains don’t care about that, so you don’t experience that.

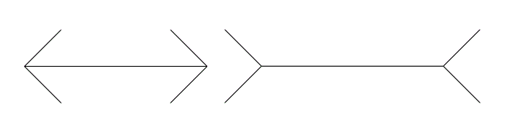

Let’s look at one last example. This is the famous Müller-Lyer illusion:

Why does the left horizontal line appear shorter than the right one? Here is the answer to that question:

Again, the brain is using whatever method evolution and training has found to be the cleanest, computationally and metabolically most efficient method of making accurate judgements about the environment. Here, the angles are used to map out the three-dimensional geometry of your surroundings. Your brain doesn’t care which line is the longest in the representational medium (screens, light, whatever).

As you might expect, the Müller-Lyer illusion is notably weaker in people that have less exposure to straight lines, corners and edges—people who don’t live in a “carpented world”7. Here’s a cool follow-up:

So, to wrap up and summarise this second (spoiler: correct) view on what’s going on with these so called illusions:

It has never been useful for us to find out how much of our retina a car or animal occupies. It has never mattered for your ancestors to know which patch of your retina is the most illuminated, or exactly which wavelenths the light there have. What has mattered are the properties of the objects out there, in the world—not in the eye or in the mind.

If experience is judgement, then to whom does it occur?

What we experience is simply the brain’s best judgement of the facts about the external world. Moreover, we experience this judgement directly. Why? It’s quite simple: judgements are what experience is made of—they are the fabric of experience.

There simply is no inner subject experiencing mental properties. That may be how most of us (I believe) narrate and model our own minds, because this model is (I believe) extremely efficient for cognition and communication.8 But as for an actual explanation for how the mind works, there just cannot be any room for an inner subject playing a role. If you want to keep the experiencing subject as fundamental in your account, then you don’t have a theory of what experience is. You have just postponed the problem!9

The Great Weirdness, then, that which deserves the word ‘illusion’ in a deeper sense, is not that the shades in the checker shadow illusion are really the same shade (they are not), or that the cars are really the same size (they are not). Rather, it is the fact that we tend expect our experience to reflect the representative medium rather than that which is represented10. If that is what we take to be going on, then everything is an illusion!

What grey and purple shade experiences teach about experiences of grey and purple shades

OK, now let’s see where all of this gets us. On the checkerboard, the brain figures out which squares are dark, and which are light. This is actually important to figure out. Does it need to figure out exactly how dark or how light the squares are? Does it have to figure out a specific shade to present to, or generate, in consciousness?11 Most certainly not—there is no reason to do so! Since there is no display of a particular shade on in an inner scene, and there is no subject there to see it, there need not be any particular shade.

But then, how come you see an absolute shade whenever you look at something? Well, again, you’re determining that the thing, out there, has definite reflective properties. Again, you are directly experiencing this judgement12.

You see, you cannot on one hand experience that stuff out there has definite properties, while it on the other hand seems to you that the experienced shade does not have definite properties. That would only make you terribly confused. Under normal conditions, you’re not going to have that experience, no matter how hard you focus your internal Mind Lasers (© Pete Mandik). You cannot outsmart this system, from the inside, because you are not a subject introspecting into the system. You are the system. There are no mirrors in the mind, and that which sees cannot see its own seeing.

This is why we, if we want to understand minds properly, must do what Dennett calls heterophenomenology—we must do the science and the philosophy of phenomenology from a third-person perspective. This is not to be taken as saying that first person reports and seemings as useless! In fact, they provide absolutely crucial data on how the mind models and narrates itself, which we need to understand the mind.

But we must take these models and narratives for what they are. We cannot afford to make the mistake of taking said models and narratives as data on how the mind actually works. That is an absolute no-go, yet plenty of professional scientists and philosophers are, unfortunately, making this mistake all the time. I hope I have managed to cast some light on why it is not a good idea.13

Back to the banana challenge

So, now prepare yourself to go back and take Mandik’s “Take Mandik’s Imaginary Purple Banana Challenge” challenge again. If you failed before, I hope that you have a a good chance of learning something deep about yourself this time (if needed: extra hint here14 and extra repetition&conclusion here15).

Good luck, and let me know how it went in the comments! Limited customer support will be available for a limited time. If no success, or if you disagree, I hope you at least enjoyed this post. Now, discuss!16

Herein, Bāhiya, you should train yourself thus:

in the seen, there is only the seen,

in the heard, there is only the heard,

in the sensed, there is only the sensed,

in the cognized, there is only the cognized.

Thus you should see that

indeed there is no thing here;

this, Bāhiya, is how you should train yourself.

Since, Bāhiya, there is for you

in the seen, only the seen,

in the heard, only the heard,

in the sensed, only the sensed,

in the cognized, only the cognized,

and you see that there is no thing here,

you will therefore see that

indeed there is no thing there.

As you see that there is no thing there,

you will see that

you are therefore located neither in the world of this,

nor in the world of that,

nor in any place

in between the two.

This alone is the end of suffering.

—The Buddha (Bāhiya Sutta, 2500-2600 years ago)

I’ve spent an embarassing amount of time just staring at this thing. Interestingly, it has significantly weakened the “illusion” for me, and much of the time A and B just look the same, without any effort.

Or intensity of full-spectrum visible light, if you prefer.

It’s worth noting that evolution has not set us up to always make the judgement that is most likely correct. Some things can be devastating to miss, so it’s better to have false positives. Face detection is a good example of that, which is why we often see faces where there are none. This “error” is a low cost compared to being worse at detecting faces.

If you said ‘no’, I suspect you somehow still thought it were a trick question.

Sure, the brain sometimes gets it wrong, but visual illusions such as those we have reviewed in this post are not really illusions in any interesting sense. They are merely examples of the brain is making accurate judgements about what matters in the world. In contrast, examples of real mistakes are when mirages make brains believe there is water ahead, or when they are convinced that there is actually a face on the moon.

And all experience, coincidentally

The extent and mechanisms remain debated, but there is more or less a consensus that there is some significant difference.

I suspect evolution basically took the physical subject-object relationship between agents and their environment, and internalised it as a model for how to manipulate and recombine memories and prior experiences into new thoughts and possible futures. Treating these simulations as objects provides a simple but excellent way of labeling, communicating, exchanging and improving both simple items and complex systems of knowledge.

These last sentences are paraphrasing one of Dennett’s central claims.

It’s worth noting that this is quite a natural illusion, for two main reasons (as I see it): first, the brain cares about what’s true about the world. Photographs, paintings and retinas, are of course, part of the world. Second, we have evolved to be extremely confident about these facts about the world when the data is clear, so that the brain (and the collective) can spend its cognitive efforts on what is not clear.

In Dennett’s words: there is no second transduction.

As I claim they are one and the same, this is in effect a tautology, but I still find it useful.

I believe there are very good reasons related to cognition, evolutionary psychology, anthropology and cultural memetics for us to rather violently resist this proposed discarding of first-person reports as data on how the mind works. Also, part of what’s going on is a simple conflation of our incredible skills at discriminating facts about the external world for an ability to discriminate facts about our own minds.

Recall, the brain does not use absolute shades. It does not use mental paint (‘figment’, as Dennett called it—he also commonly phrased this as “there is no second transduction”). There is no Cartesian Theater in which an inner subject sees the mental show of consciousness filled with particular shades and colours.

Colour experience is, like all experience, conceptual and contextual. There is no fact of the matter about which shade of grey or purple you experience, because there is no mental palette of mental colours from which the brain chooses and generates experiences.

Feel free to support me too by suggesting structure edits or layout changes or omissions or pointing out errors to improve the post. This is most welcome. I know it’s a bit of a mess.

As a cognitive scientist, I'm very familiar with the visual illusions and ideas around how they work, but I am confused by your post.

I have synethesia, including color-letter mapping, and each letter is a very specific color to the extent that m and t are very different shades of red, while d,g,p,s, and z are all different shades of green. The color is part of the concept of that letter, but it's a specific color. And I've participated in work that has shown the color is precise and stable over time for me and other synesthetes.

Incidently, with the purple banana, my reaction to the shades of purple was to be frustrated because my purple is much bluer than any of the options presented.

Great piece! It might be a bit strong to say all “experience is always conceptual.”

Do you think that babies experience? If yes, do they do so with or without concepts?

I think trivially babies experience. The question is, do babies come with innate concepts or not? If no, then there are instances of non-conceptual experiences.

I’m happy with innate *abilities to conceptualise* in various way, but it’s more contentious to say that the *concepts themselves* are innate.